Oppenheimer’s Biggest Blunder: Frozen Stars

[Adapted from Chapter 7 of Crush: Close Encounters with Gravity]

A few years before he headed to Los Alamos, New Mexico to build the world’s first nuclear weapon, J. Robert Oppenheimer made the biggest blunder of his academic career.

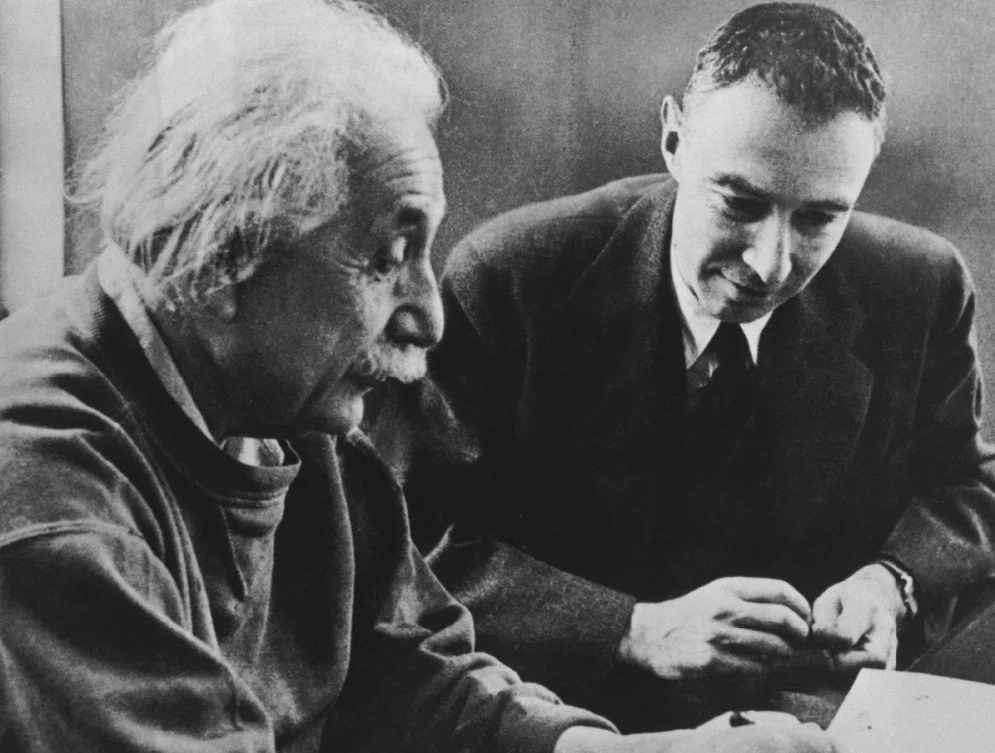

Einstein and Oppenheimer in the 1950s, when Oppenheimer thought most black holes were really stars frozen in mid-collapse and Einstein didn’t believe in black holes at all.

In a paper in the Physical Review journal, Oppenheimer claimed that black holes can never form in reality because, as he and his coauthor Hartland Snyder wrote, “it is impossible for a singularity to develop in a finite time.”

A singularity is the infinitely dense point assumed to be at the center of a black hole. If it can’t develop in a finite time, then anything that could lead to a black hole should take an infinite amount of time to do it.

A prenatal black hole, as Oppenheimer and Snyder saw it, would end up freezing for all eternity, just short of becoming a fully developed black hole.

We now know that their description of what some people later came to call frozen stars was as wrong as wrong can be.

Frozen Star Fallacy

In reality, true black holes are quite common. A rough estimate puts their number at fifty million billion in the part of the universe that we can see.

Many black holes are the end products of dying stars. As a star runs out of fuel, the outer portions explode in a hot, bright burst that is a supernova. The central portion then collapses. In as little as a fraction of a second, the matter that was once the core of a star is densely compacted into a black hole’s singularity. This is the process that Oppenheimer and Snyder at least partially explained in their paper

They found in their calculations that such a collapse would happen quickly for the material that once made up the star. Their mistake was in claiming that, from the perspective of anyone watching from afar, the collapse would take an eternity.

The myth of the infinitely slow collapse toward, but never truly reaching, black hole status was a pernicious one. In Russia, in particular, the idea was so pervasive that frozen star became the widely accepted name for what supposedly resulted from grindingly slow progress toward forming a black hole singularity.

It’s an error that was propagated in the decades that followed by such black hole luminaries as Roger Penrose in 1965, Werner Israel in 1966, and Remo Ruffini together with John Wheeler in 1971.

How did Oppenheimer and Snyder end up so far off base? And why were so many brilliant scientists taken in by it for decades? Here’s my guess.

Black Hole Blues

Essentially, Oppenheimer and Snyder were thinking in terms of what happens to time near very dense things. That’s where gravity gets intense. In terms of warped spacetime relativity, it’s where the curvature of spacetime becomes extreme. In places where that happens, time slows down.

It’s an effect known as time dilation. We can measure it here on Earth, even though gravity (and spacetime curvature) is fairly mild. A clock at sea level runs a bit slower than one on a mountain because the lower clock is closer to the mass of the Earth.

For someone sitting still near a black hole, time slows in the extreme. At the event horizon that marks the outer edge of a black hole, gravity is so intense that if a clock were somehow anchored there, it would come to a complete stop.

In considering a collapsing star, Oppenheimer and Snyder noted that time would slow more and more as the density of the stellar remnants increased further and the nearby gravity soared. Time wouldn’t come to a stop entirely, but the star’s core would never become a full-fledged black hole singularity in a finite amount of time. It would only approach black hole status at a perpetually slowing rate, never reaching it.

For someone falling in with the collapsing star material, Oppenheimer and Snyder correctly realized, there would be no change in time. (You’re watch always ticks at the same rate for you because it’s in your reference frame.) To those of us watching from afar, we’d see a person sitting still near a dense, almost-but-not-quite black hole experience extreme slowing of time.

This is where Oppenheimer and Snyder went wrong in their interpretation. For a clock to still near a dense object where gravity is intense, it would need a rocket engine to accelerate it upward to oppose gravity. It’s the acceleration against gravity in order to stay still that leads to time dilation.

The freely falling material in a collapsing star never sits still. It’s not accelerating against gravity, and if you were riding along with the collapse, neither would you.

In 1967, Kip Thorne published a popular science article in Scientific American that corrected the mistake of Oppenheimer and Snyder.

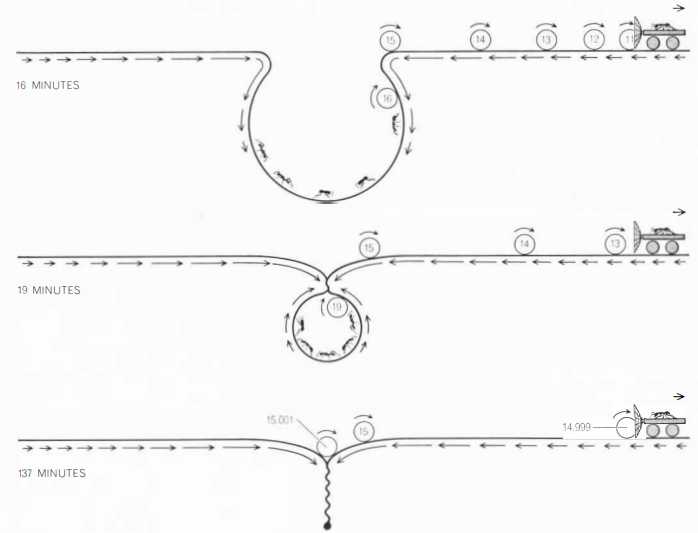

This is a portion of Kip Thorne’s illustration using ants to explain why a “frozen star” is an illusion, and that sufficiently massive stellar cores left over after supernovas never slow, from any perspective, as they collapse to become black holes. ~Scientific American, November 1967, page 96.

Thorne based his magazine article on an analysis that Wheeler’s research group members, David Beckedorff and Charles Misner, had thought of a few years prior. Thorne’s piece is worth a read if you have access to old copies of Scientific American. Or you can see it on page 246 of Thorne’s book Black Holes & Time Warps.

Below is the simplest way I can think of to explain it.

The Escape Velocity/Freefall Connection

First, you need to know about escape velocity. If you used a cannon to shoot a projectile upward, the faster you fired it, the higher it would go. Fire the cannonball fast enough, and it will sail infinitely far away. The velocity that’s just enough to hurl the cannonball so that it will never come back down is the escape velocity. At sea level on Earth, escape velocity is 40,270 kilometers per hour.

The event horizon of a black hole exists where the escape velocity equals the speed of light. That is, a cannonball fired at the speed of light would be fast enough to escape to infinity from just outside the event horizon. Inside the event horizon, the escape velocity is faster than the speed of light. So your lightspeed cannonball, and light itself, can’t escape at all if it starts from inside the event horizon.

You can turn things around to consider what happens if you were to go infinitely far away from the Earth and release a cannonball (you’d have to give it a tiny nudge to get it going).

As it fell toward us, it would accelerate until it reached the ground at the same speed it took to hurl it infinitely far away. That is, the cannonball’s speed upon reaching the ground from infinity is the same as the escape velocity it would take to go to infinity. It’s just going in the other direction.

In other words, as something falls toward the Earth, or a star, or a black hole from far enough away, its speed down at any point is the same as the escape velocity at that point.

If you were to fall toward a black hole from infinity, your speed at the event horizon would be the speed of light because that’s the escape velocity at the event horizon.

Escape velocity increases further the closer you get to the singularity at the center of a black hole, and reaches infinity at the singularity.

Because your free-fall speed toward a black hole is the same as the escape velocity at any given point along the way, you won’t slow down at the event horizon. You careen past it at the speed of light and continue accelerating to infinite speeds (with respect to a distant fixed point) by the time you get to the central singularity.

Clocks and time dilation don’t come into this simple analysis at all. Relative to a person sitting far away, you fall toward a black hole just as you would toward anything with mass. There is no strange slowing that kicks in as you approach, reach, or pass an event horizon.

Although you would fade from view as a distant observer saw it, your speed relative to that observer only increases as you plunge all the way into the central singularity.

Time to Fall Into a Black Hole

Suppose you were to stumble into a black hole. In that case, the time it would take from your perspective to make it from the event horizon to the singularity is the exact amount of time a distant observer would calculate that the journey takes relative to them.

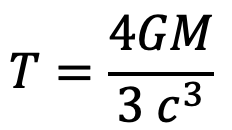

Specifically, the equation for the duration of the trip, from either your perspective or the perspective of a distant observer, is

Where T is elapsed time, G is Newton’s gravitational constant, M is the mass of the black hole, and c is the speed of light in space (299,792,458 metres per second). Plugging in the values for a black hole with ten times the mass of the Sun results in an elapsed time to fall from horizon to singularity of 66 millionths of a second. (You can play around with the equation, and choose other black hole masses, on this Wolfram Alpha page.)

If you can fall to the center of a black hole that fast, then a collapsing supernova core will get there just as quickly.

Black holes clearly form almost immediately after a supernova blast, both from the viewpoint of someone riding with the collapsing star and that of someone located far away. In neither case is the outcome of a supernova the infinitely slow transformation that Oppenheimer and Snyder proposed.

Blunder or Triumph?

In one sense, the 1939 Oppenheimer/Snyder paper is a landmark triumph in relativity theory. It was the best attempt up to that time to describe how a black hole could form after a supernova.

Although the paper includes some dubious simplifying assumptions (a non-spinning star to begin with, the lack of any internal pressure resisting the collapse, etc.), the analysis inspired a generation of astrophysicists to look more deeply into the implications of Einstein’s relativity.

It was an important advance in the field, at least as far as considering the collapse of a star from the perspective of an observer riding along with the infalling material. In that sense, the paper is truly a triumph.

The fallacy of frozen stars, however, was a serious blunder. Without a doubt, we now know that Oppenheimer and Snyder were completely wrong in that portion of their interpretation.

But for more than forty years after the paper was published, many people believed in frozen stars and had doubts about the existence of what we now know to be a very real and substantial population of black holes in the universe.

The repercussions of the Oppenheimer/Snyder blunder are ongoing. There are still plenty of people embracing the frozen star fallacy today, including one of my favorite science explainers on the YouTube channel The Action Lab:

Skip to 6:15 in the video to see where they present the now-debunked interpretation of Oppenheimer and Snyder. The problem again is the emphasis on time dilation, and misunderstanding about how it affects objects in free-fall toward a black hole.

Frozen Star Illusion?

It’s true that anything approaching a black hole will appear to a distant observer to slow down when it nears the event horizon. Oppenheimer and Snyder misunderstood it as indicating the actual slowing of free-fall near the event horizon. Others, including Thorne, have described it as an optical illusion.

Thorne shows in his Black Holes & Time Warps book that the photons coming from a free-falling astronaut are both reduced in energy (redshifted) and delayed in their escape by the intense gravitational field. After an astronaut passes through an event horizon, photons in the trail of light they left behind continue to emerge, at lower and lower energies, long after the astronaut has passed.

I find the idea of an optical illusion to be too generous. The situation is more akin to the lingering stench that wafts on a breeze in the moments after a garbage truck has barreled down the road. The smell left over isn’t what I would call an image of the stinky truck. It’s an artifact that remains as evidence that the garbage truck had once been near.

Whether we’re discussing photons trickling outward from the edge of a black hole or foul molecules drifting in the wake of a garbage truck, each is a feeble memento left in the paths of the speedy objects that produced them. They aren’t images of the objects as they currently appear.

The “image” of a traveler pasted just outside the event horizon will fade and redden, eventually turning into extremely low-energy radio waves. It’s less like an image than a degrading trail of photon bread crumbs.

Image, illusion, or bread crumbs, the light left behind by someone or something falling through a black hole event horizon says next to nothing about how fast they were falling. Analyses like the one that the Action Lab presents in the clip above, however, confuse the photons we later see with the motion of the falling object itself. I’m hopeful that the science, as Thorne describes it (and I tried to show above), will help to clear up that confusion.

The bottom line is this: from any perspective, black holes are not frozen stars.

In their interpretation of collapsing stars remaining stuck in place, just shy of becoming black holes for all eternity, Oppenheimer and Snyder seriously goofed. We pay a price for their error every time someone invokes the fallacy of frozen stars.

***

Do you have thoughts about this post, or anything else about gravity or relativity? Use the form below to drop me a note, or sign up to stay in the loop on posts to come.

-James