Einstein’s Black Hole Error (and an Easy Fix)

Black holes are infinitely deep pits of gravity. They’re among the startling predictions of Albert Einstein’s general relativity.

They’re so bizarre that when Einstein first learned of black holes lurking about in the math of relativity, he declared that they couldn’t exist in reality, no matter what his own theory said.

The black hole at the heart of galaxy M87 is the first one ever photographed. NASA scientists captured this image of the black hole in 2017. The M87 black hole is surrounded by the glow of material falling in and getting superheated on the way.

The problem, as he saw it, is that anything that fell into a black hole would end up traveling faster than the speed of light. He had built general relativity in part on the axiom that light sets the ultimate speed limit in the universe. Nothing could ever move faster than light. That made black holes paradoxical.

Probably, Einstein reasoned, black holes were a quirk of the math that we should simply ignore their appearance in general relativity.

He was flat out wrong about that.

There is no question today that black holes exist. We have photographs like the one above to prove it, and the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO) records dozens of gravitational wave chirps every year that come from black holes colliding far off in space.

Gas glows brightly in this computer simulation of supermassive black holes only 40 orbits from merging. Credit: NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center

How did Einstein get it so wrong? There are two possibilities that I can think of.

First, the version of relativity that Einstein relied on is hard. It depicts the universe as a blend of space and time, forming four-dimensional spacetime. Unfortunately, as humans, we are used to three dimensions of space (up and down, back and forth, left and right) and one dimension of time. Few, if any, people can envision four dimensions. That makes interpreting the predictions of warped spacetime relativity difficult.

The second problem seems to have been Einstein overlooking a key point of his own rule:

Light always travels in empty space with a definite velocity c.

(Where the speed of light, c, is exactly 299,792,458 meters per second.)

Considering that nothing can travel faster than light, this statement implies that nothing can travel through space faster than c. This is absolutely true. It’s the space that gets weird near anything with mass, especially black holes.

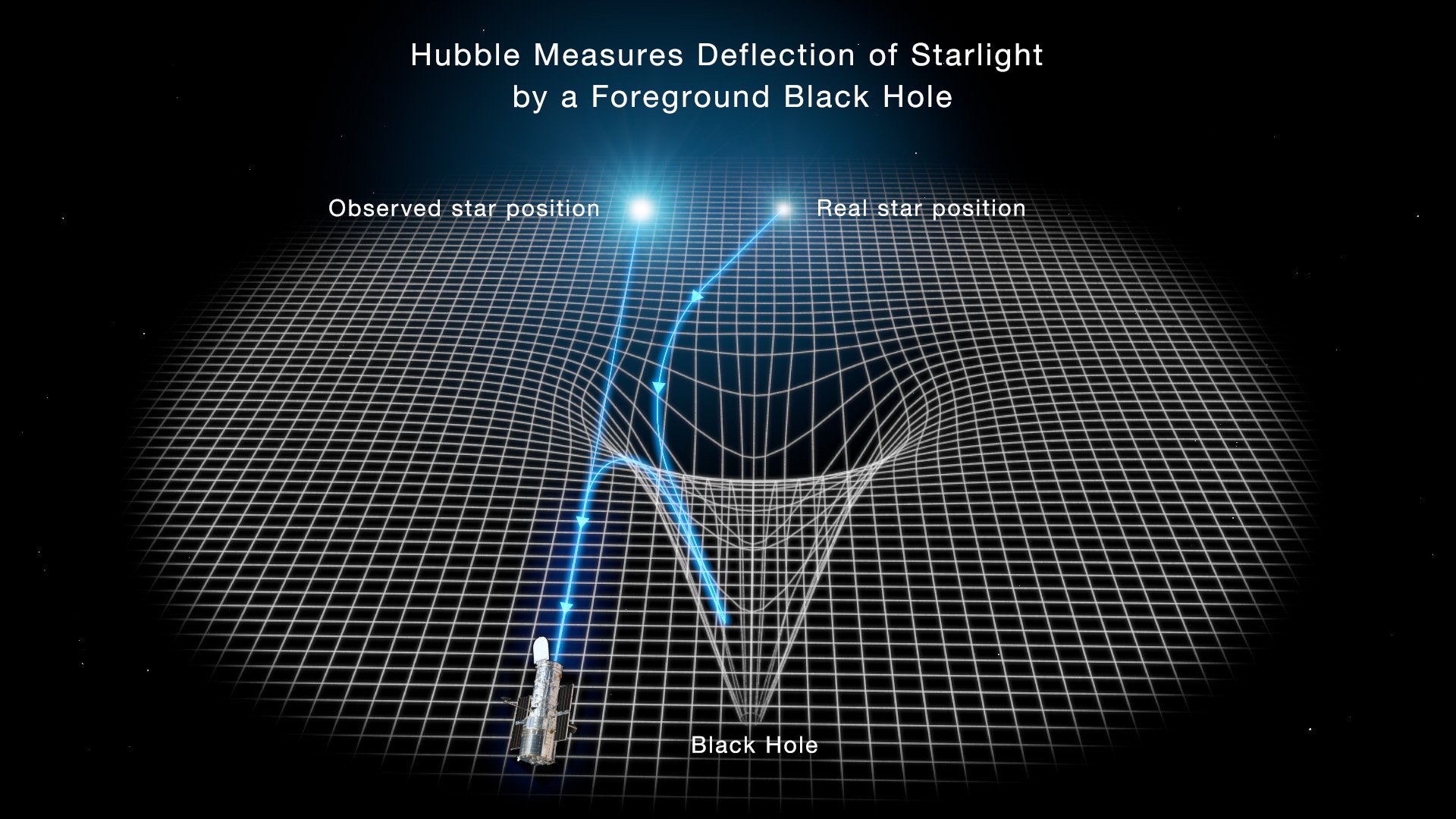

A black hole warps spacetime in Einstein’s interpretation of relativity, which bends the path of light from a distant star. Image credit: NASA

It’s interesting that, of all people, Einstein would get things wrong when it comes to black holes. The image above may illustrate why.

Though a fairly simple illustration of the warping of spacetime, it leaves out an important feature — there’s a missing dimension. This sketch uses three dimensions to depict what’s going on in two dimensions of space. There aren’t enough dimensions that we can draw in order to show the effect on three-dimensional space that results from the warping of a four-dimensional spacetime.

What’s more, this sketch doesn’t seem to offer a good way to see the key feature of a black hole — the event horizon that marks the point of no return for light or anything else that ventures too close.

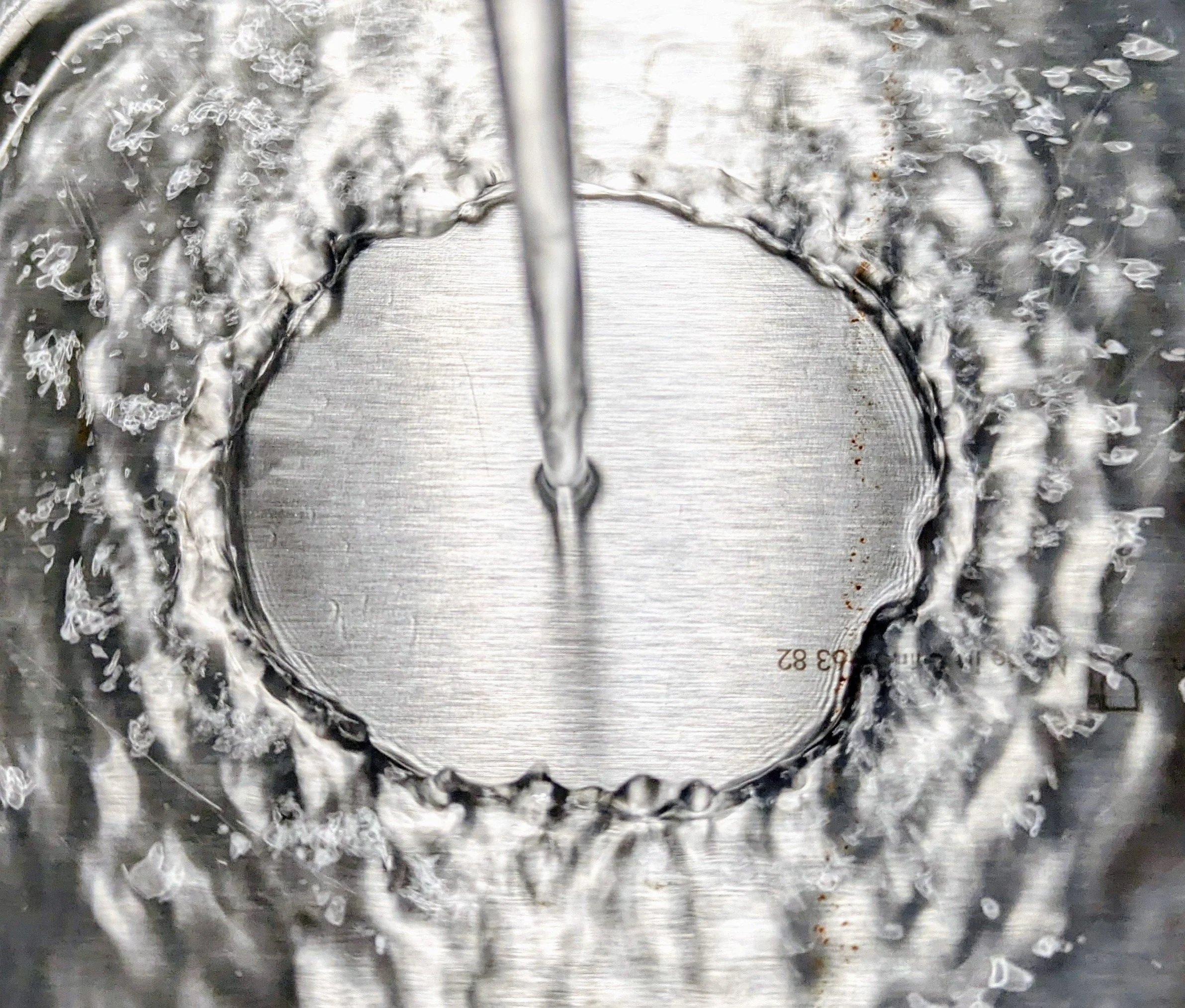

Had Einstein turned to the coordinates that researchers in 2011 used to describe the liquid black holes that are the subject of my kitchen sink black hole posts in part 1, part 2, and part 3, I’m sure he would have been more optimistic about the existence of black holes in space.

A Flowing Space Solution

Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates are conceptually and mathematically simpler than the coordinates Einstein used. The conceptual simplicity is due to the fact that the coordinates involve familiar, three-dimensional space, rather than warped spacetime. That leads to the mathematical simplicity because you don’t need the sort of advanced mathematics that four-dimensional spacetime demands. Simple geometry, algebra, and a bit of elementary calculus is all it takes to study black holes in Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates.

The approach comes with some weirdness to account for the features of relativity. In Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates, space itself flows just like water does in kitchen sink black and white holes.

Both the pattern that water forms when a stream hits the basin of your kitchen sink and the structure of basic black holes are simple in Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates.

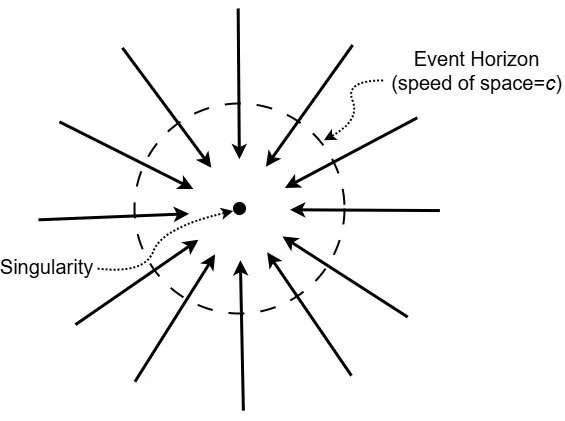

In flowing space relativity (also called the river model), space flows towards mass. The larger the amount of mass and the closer you are to it, the faster space flows. For black holes, the flow of space eventually reaches and exceeds the speed of light as it heads toward an infinitely dense point called a gravitational singularity.

As a result, it’s trivially easy to figure out where the event horizon is. The event horizon is where the speed of space flowing toward the singularity of a black hole is equal to c.

For a black hole in the flowing space relativity of Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates, finding the event horizon is easy — it’s where the speed of flowing space equals c.

Although Einstein was aware of Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates, and acknowledged that they are a legitimate way to do relativity calculations, neither he nor anyone else realized how much easier they make the subject.

Black holes in flowing space are the simplest example. But just about anything that you can describe in 4D warped spacetime relativity is easier in the 3D flowing space interpretation of relativity.

I’ll get into some other applications of flowing space relativity in future posts. For now, I’ll leave you with the easy flowing-space calculation of the size of a black hole event horizon.

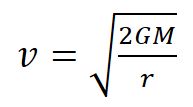

In Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates, space flows toward anything with mass at a velocity that depends on the total mass M, Newton’s gravitational constant G, and the distance from the center of mass r.

Note: I forgot to include the factor of 2 in a previous version of this post.

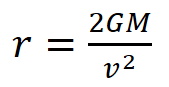

You can rearrange this to solve for r.

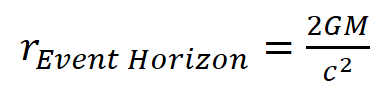

At the event horizon, the velocity of space is the speed of light, so substituting c in for v, leads to an equation for the radius of a black hole event horizon.

That’s it. Some simple algebra is all it takes, and you have the answer for the size of a black hole event horizon. What’s more, you don’t need to be an Einstein to do it.

Check out this video to see how much more complicated it is to find event horizons in warped spacetime. They arrive at the solution at 9:02. This is as clear as it gets in warped spacetime calculations. Enjoy!

If you stick with the simple equation we found above, plug in the values for Newton’s gravitational constant (G), the speed of light (c), and a black hole mass (M), to tell how big a black hole event horizon would be. For a black hole with the mass of the Earth, the event horizon would be about the size of a gumball, roughly a centimeter across. A black hole with the mass of the sun would be about 3 kilometers in radius. If a black hole weighed as much as I do, the event horizon would be ten billion times smaller than a proton.

In case you want to play around with event horizon sizes, here’s a link to the calculation on the Wolfram Alpha webpage. I already entered the values for G and c, along with the mass of the Sun for M, to get you started. Try other masses to see how big a black hole would be if it weighed as much as things like Jupiter or the whole Milky Way.The answer at the bottom of the calculation page is in meters.

***

For an equation-free dive into the flowing space interpretation of relativity, take a look at my book Very Easy Relativity. Subscribe to my email list, and I’ll send you a PDF for free. Just click the “Send me the PDF” option in the form below.

Or, if you want to see the equations of flowing space relativity, check out Relatively Easy Relativity instead.