The One Orbital Effect You’ve Never Heard of

[Adapted from Chapter 6 of Relatively Easy Relativity]

It was one of the first triumphs of general relativity. In 1915, Albert Einstein used his brand-new theory to explain a puzzle in the orbit of Mercury.

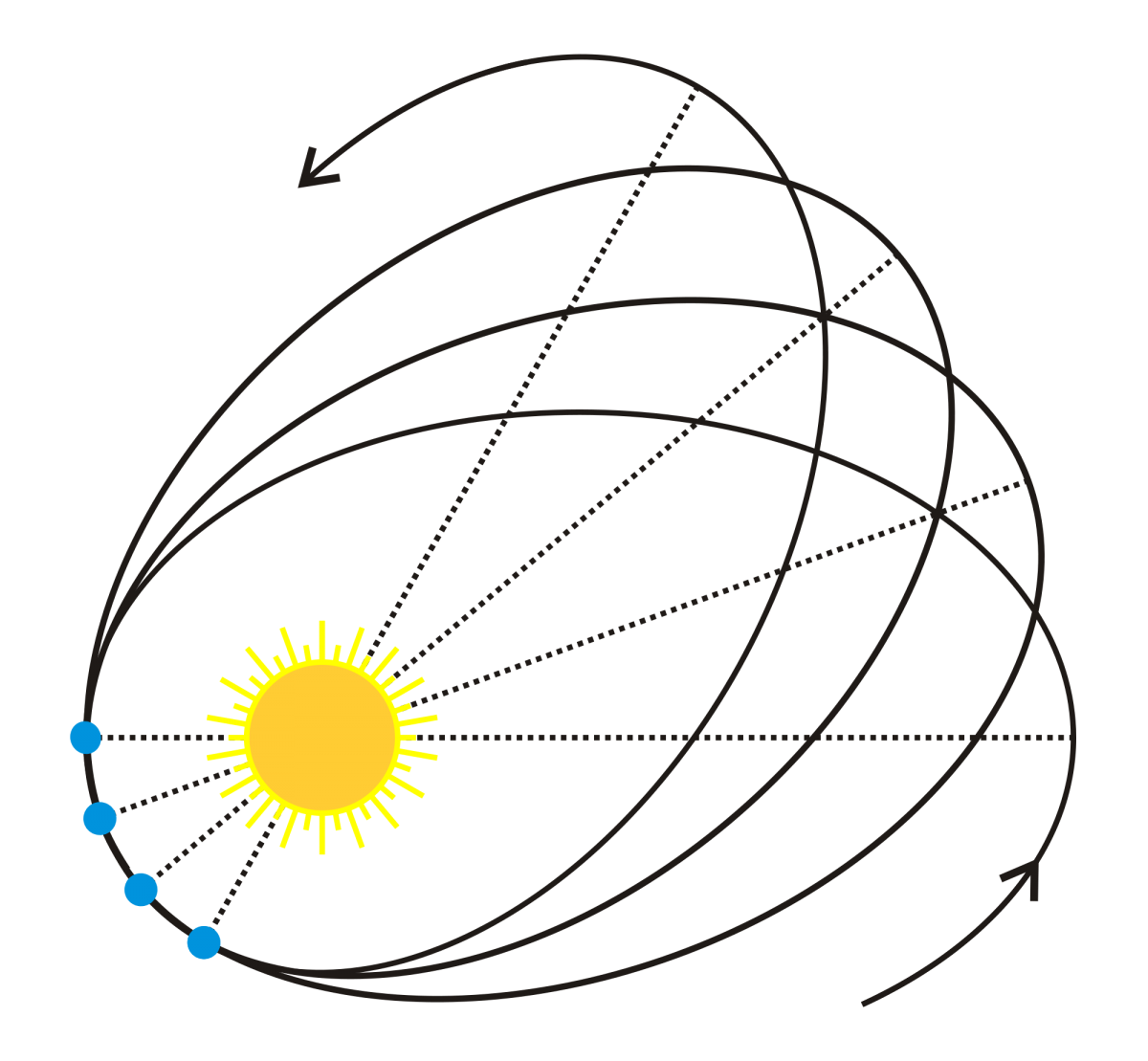

Like all the planets, Mercury travels around the Sun on an elliptical path rather than a circle. The influence of the other planets causes the ellipse to swing around, resulting in a looping Spirograph-like pattern. It’s known as orbital precession.

The ellipse of Mercury’s orbit precesses due to interactions with the other planets, the shape of the Sun, and three relativistic effects that were unexplainable before Einstein came along.

While Newton’s law of universal gravitation explained most of Mercury’s precession, about 7.5 percent of it is due to relativistic effects.

There’s a good chance you’ve heard of one relativistic effect on the motion of Mercury: geodetic precession, which is the formal term for the precession Einstein explained for Mercury. If you’re a science nerd (like me), you might have heard of the second: Lense-Thirring precession.

The third effect, though, is so small and so obscure that it doesn’t seem to have a name, as far as I can tell.*

Let’s look briefly at all of them, from the largest precession effect to the smallest.

Einstein’s Triumph — Geodetic Precession

Geodetic precession accounts for most of the relativity-related precession of Mercury. The effect is due to the mass of the Sun, and it amounts to about 43 arcseconds per century.

That’s one ten-thousandth of a degree in a year. If you held out a human hair at arm’s length, it would look ten times wider than the angular shift in Mercury’s orbit each year due to Geodetic precession.

Astronomers had noted for centuries what came to be known as the anomalous precession of Mercury. But it took Einstein and his general relativity to solve the mystery.

Relativity, though, doesn’t stop there. A second relativistic effect, Lense-Thirring precession, is 215,000 times smaller than the geodetic precession of Mercury — and it’s going the other direction.

Lense-Thirring Precession from Frame Dragging

At a mere -0.002 arcseconds per century shift in Mercury’s orbit, Lense-Thirring precession is far too small to have gotten the attention of astronomers before the advent of Einstein’s relativity. Even today, Lense-Thirring precession is just beyond our measurement capabilities when it comes to tracking the planets’ motions around the Sun.

The effect can be explained in terms of frame dragging in combination with Mercury’s orbit. As usually described, the Sun’s spin drags spacetime around with it. Mercury is orbiting the the same direction as the Sun’s rotation, and therefore with the dragging of the spacetime frame.

In the case of Mercury, it’s effectively orbiting ever so slightly slower with respect to the spacetime frame because it’s going the same way.

The situation is much like a pair of friends changing gates at an airport. Suppose one chooses to take a moving sidewalk, and the other doesn’t. If they want to stay together, the person on the sidewalk has to walk a bit slower relative to the moving sidewalk than their companion moves relative to the solid ground. The result is that they can proceed at the same speed.

For Mercury, the dragged frame is comparable to the moving sidewalk. Although the planet’s orbital speed as we see it is the same as it would be if there were no moving frame, the planet moves more slowly relative to the dragged frame because they are both in the same direction.

The slower orbit with respect to the dragged frame reduces the amount of orbital precession that Mercury experiences. That’s why there’s a minus sign in front of the Lense-Thirring precession for Mercury.

If Mercury were going the other way around the Sun (retrograde orbit), it would be moving against the Sun’s rotation. That would increase Mercury’s speed with respect to the Sun’s dragged spacetime. As a result, Mercury would experience a positive Lense-Thirring precession, which would add to the roughly 43 arcseconds per century that comes from geodetic precession

Some researchers are hopeful that we’ll detect Lense-Thirring precession for Mercury, and possibly other planets, soon. In the meantime, a high-precision experiment closer to home has confirmed the effect.

Gravity Probe B was a satellite that orbited the Earth from 2004 to 2010. In that time, changes in its orbit accumulated enough to measure both the geodetic precession resulting from the Earth’s mass and Lense-Thirring precession caused by relativistic frame dragging.

Lense-Thirring precession depends on both the direction of the planet’s (or satellite’s) orbit and the spin of the star (or planet) being orbited. While geodetic precession is the result of the mass of the object being orbited, as well as the speed (but not direction) of the object in orbit.

There is a third, and final, relativistic contribution to orbital precession that is so small and obscure that, as far as I can tell, it has no name.

Finally, the Nameless Orbital Precession You’ve Never Heard of

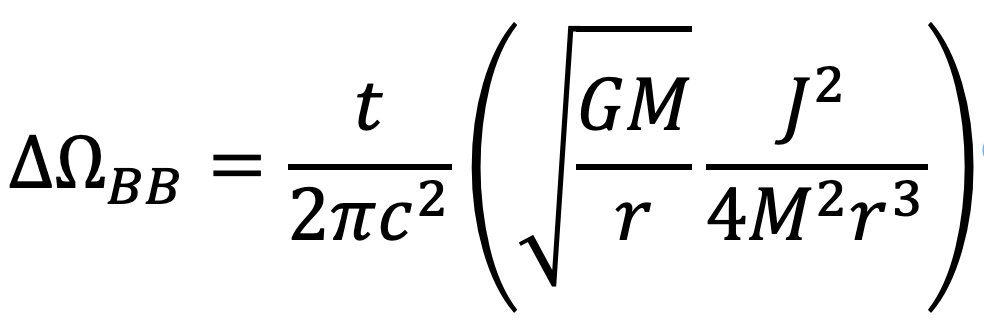

Geodetic precession accounts for less than a tenth of the shift in Mercury’s orbit. Lense-Thirring precession is two hundred thousand times smaller still. But even that dwarfs the third, as yet unnamed, precession effect. For the time being (at least until I hear if it already has a name), I’ll call it BB-precession, and refer to it with the expression

The triangle symbol is the Greek letter delta, meaning change. The upside-down horseshoe is the Greek letter omega, which I use to indicate the angular position of a planet in its orbit. And the BB subscript is just a name I’m using for the effect until I learn of a formal term.

Unlike geodetic and Lense-Thirring precession, BB precession is due to the spin and mass of the Sun, not the motion of the planet in its orbit. That is, it’s the result of the Sun’s angular momentum.

For Mercury, the BB precession is in the direction of the planet’s orbit. Like geodetic precession (and unlike Lense-Thirring precession), BB precession increases the advance of Mercury’s orbit in its swing around the Sun. However, the contribution is tiny.. It only accounts for 4.2 billionths of an arcsecond of Mercury’s orbital precession per century.

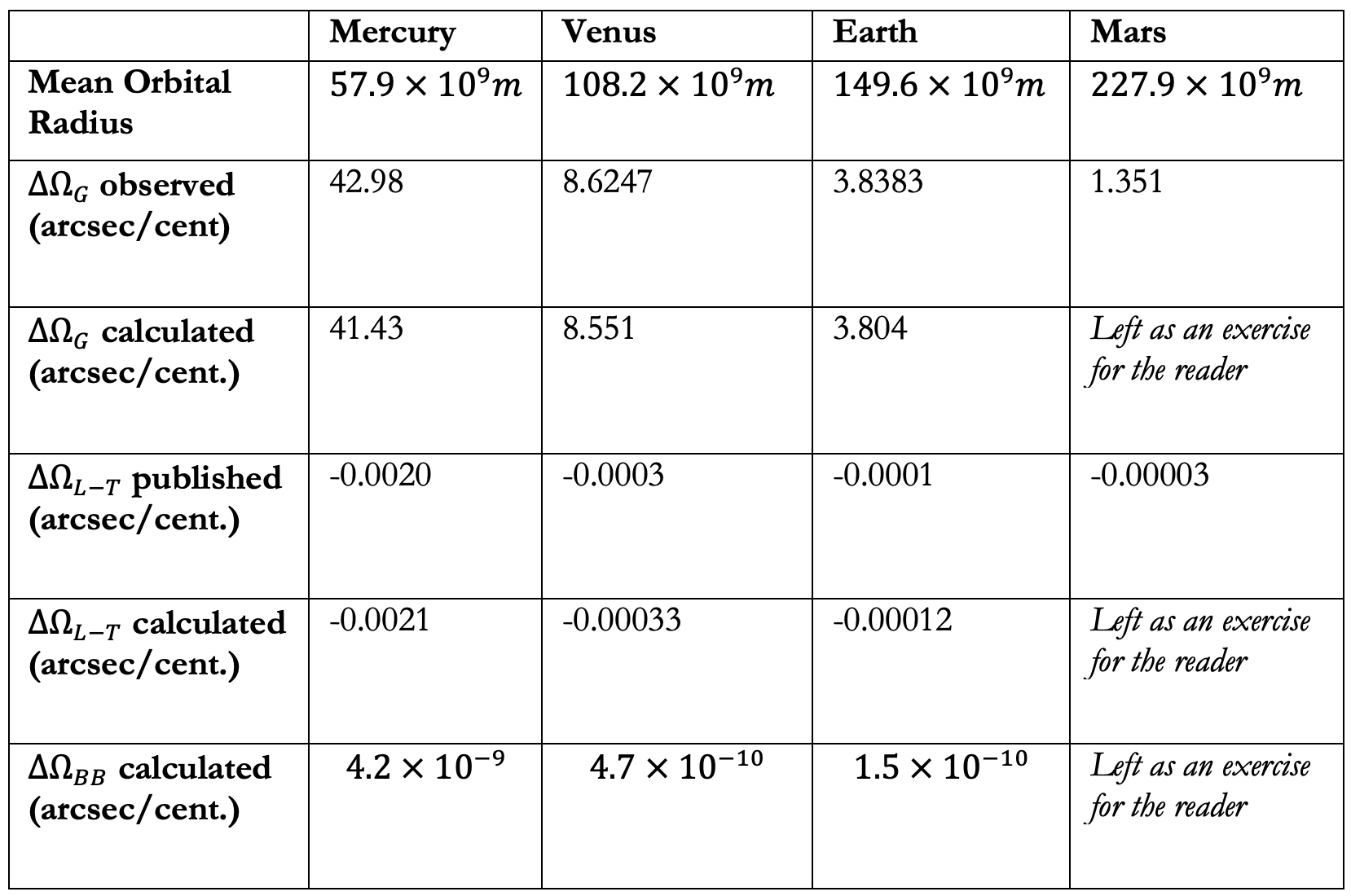

(See the table below for a comparison of the effects for Mercury and other planets.)

That’s half a million times smaller than Lense-Thirring precession for Mercury and 10 billion times smaller than the planet’s geodetic precession.

Considering we can’t quite measure Lense-Thirring precession even now, it’s hard to guess how long it will take before anyone will be able to check for BB precession of planets. Experimentalists are clever, though, so I would never predict that it’s impossible.

There you have it, BB precession is the relativistic effect you’ve probably never heard of before. Considering how minuscule it is, and how difficult it will be to ever measure, you may never hear of it again.

***

The Mathy Bits

For anyone curious about the mathematical details that go with this blog post, here are the equations for the three relativistic precessions.

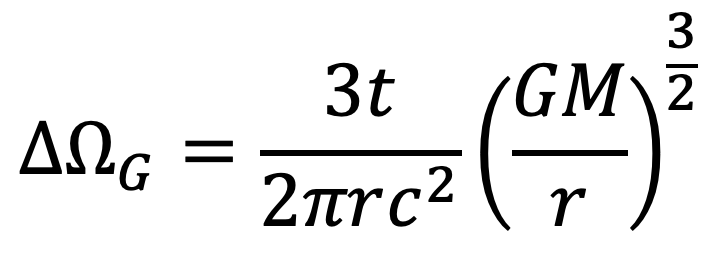

Geodetic precession:

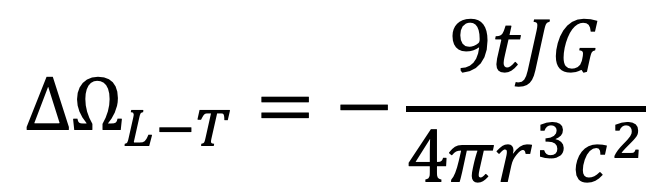

Lense-Thirring precession:

BB precession:

(Note: In order to avoid awkward exponents, I didn’t collect all the r terms in the expressions for the geodetic and BB precessions.)

The factors in the equations are Newton’s gravitational constant G, the mass of the Sun M, the average size of a planetary orbit r, the speed of light c, the angular momentum of the Sun J (that’s the spin-related part), and the time t in seconds.

Here’s a table where I compiled the values for the three types of precession for Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, as calculated with the equations above. For comparison, I included the best published values currently available:

To share the math fun with motivated readers, I left some values for the precession of Mars out of the table. Units here are arcseconds per century.

As you can see in the table, the observed values for the geodetic precessions of the planets (second row of data) and the calculated (third row) agree well. They would have been closer, except that I made the simplifying assumption that the orbits are circular, rather than ellipses, when I derived these equations — it makes the math a lot easier, at the expense of some accuracy.

Accepted values for the Lense-Thirring precessions of the planets (fourth row of data) are available in a paper by L. Iorio. They, too, are in close agreement with the calculated values (fifth data row) in the table above.

As far as BB precession is concerned, I have yet to locate a calculation of the values for the planets in the literature. Considering that I derived all three of these precession effects with the same approach, I’m guessing the BB precession values are correct as well (bottom row).

Check out the details that led to the equations and table above in Chapters 4 and 6 of Relatively Easy Relativity.

For questions or comments about this post, or to find out why I call the otherwise nameless effect “BB precession,” you can reach me through the form below.

*In particular, if you know of a formal name for what I’m calling BB precession, please share it with me! I’ll deeply appreciate it.