Gravity isn’t Geometry, according to Einstein

“I cannot agree with the widespread view,” Einstein wrote in 1948 *, “that general relativity 'geometrizes' physics.”

Einstein’s perspective puts him at odds with today’s widespread mantra that gravity is, fundamentally, the result of the geometry of warped spacetime. This wasn’t Einstein being contrary or flippant— it was a view that he held his entire life.

Is it, perhaps, another example of Einstein misinterpreting his own theory of general relativity? Afterall, Encyclopedia Britannica, NASA, and Brian Cox can’t be wrong.

Or can they?

To his credit, Neil deGrasse Tyson is more cautious — he’s not sure what gravity is, even though he knows what it does.

Still, Tyson attributes to Einstein the very opposite of the view expressed in the quote at the top of this post.

“Einstein,” says Tyson, “would say gravity is the curvature of space and time.”

It’s a compelling idea. A baseball in flight, a planet in orbit, and even light all move on paths that are actually straight. They only appear to follow curves because they’re traveling through warped spacetime.

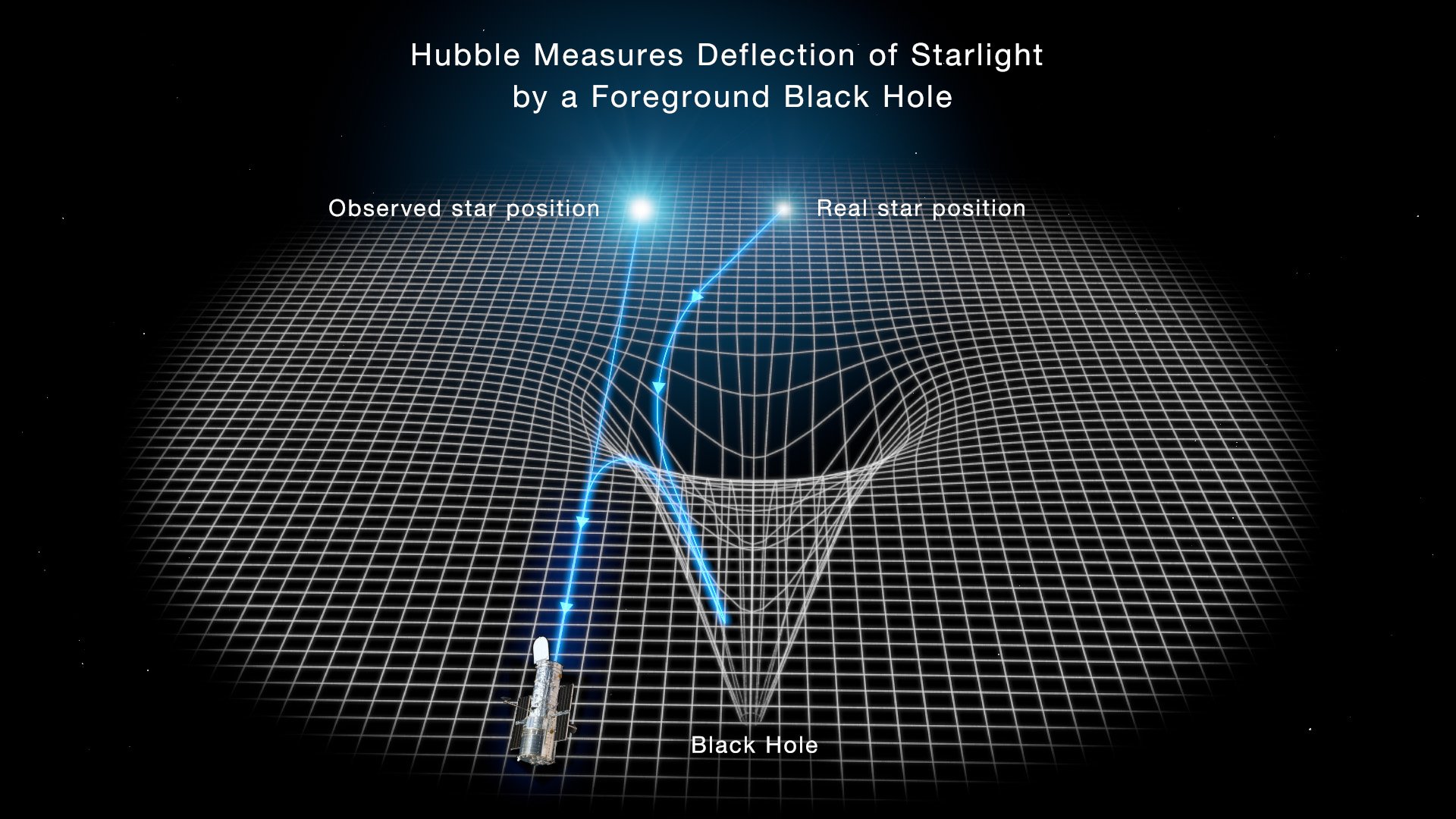

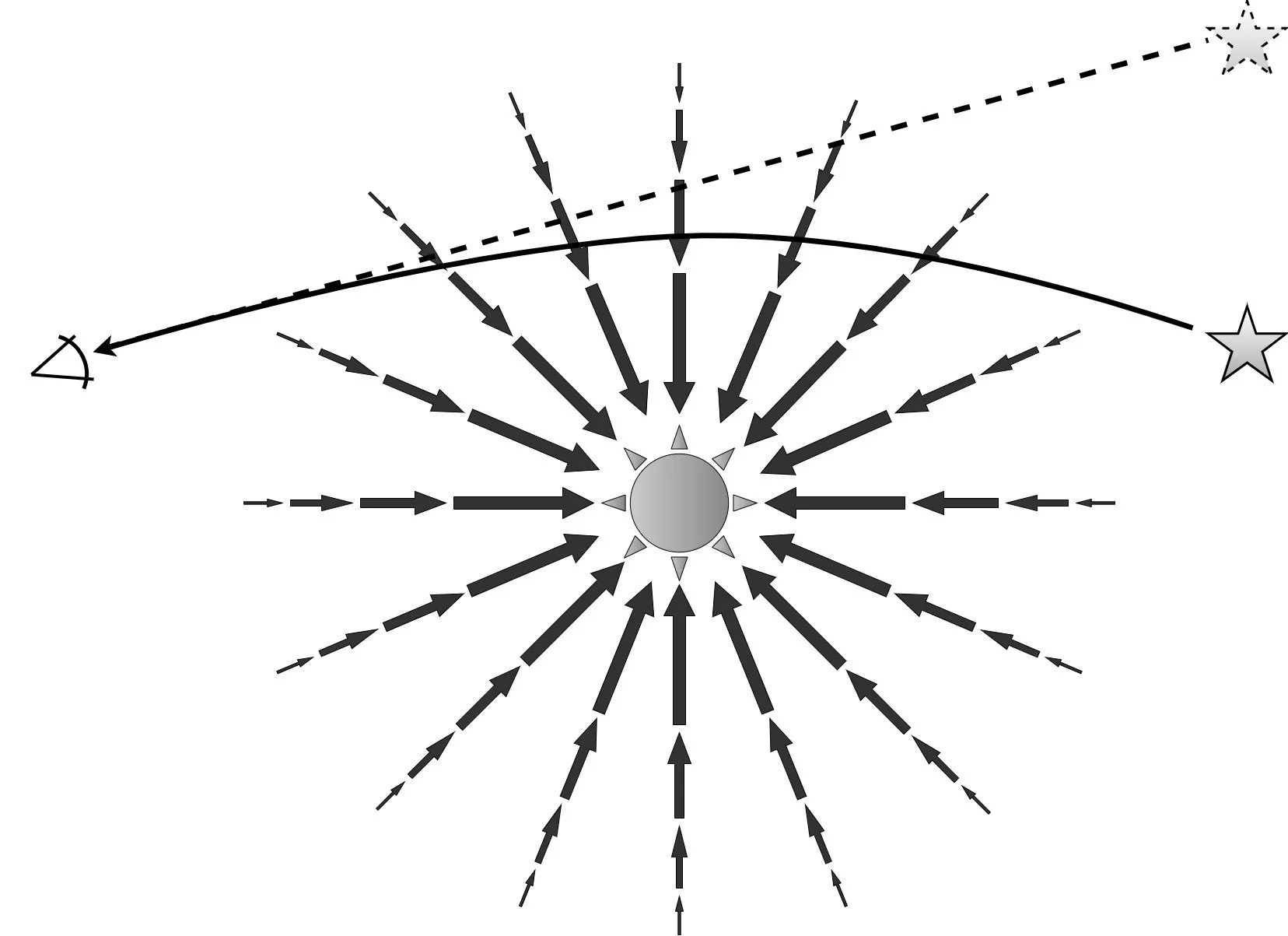

Warped spacetime offers one explanation for the displacement in the apparent location of a distant star. See the diagram below for another explanation.

What’s more, the force that your science teacher once told you was gravity pulling you down isn’t a force at all. It’s the Earth pushing you off the straight line in warped spacetime that you would follow if a hole in the ground suddenly opened below your feet.

To many people, the success of general relativity in describing the universe is definitive proof that gravity is geometry. What could have possessed Einstein to doubt it?

I’m not going to pretend to know what was in his mind. But there’s at least one thing that Einstein knew of that suggests the geometry of warped spacetime not the only way to explain gravity.

In 1921 and 1922, Paul Painlevé and Allvar Gullstrand independently proposed a set of coordinates for relativity where there is no warping of spacetime. Instead, space flows in Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates.

Rather than following straight lines in warped spacetime, baseballs, planets, and light move along paths that are bent by currents of space.

Instead of following a straight line in warped spacetime, in Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates, the path that light takes is bent as it passes through a current of flowing space. Either interpretation leads to the same prediction for things like the gravitational deflection of light around stars, black holes, or other massive objects.

To be clear, there is nothing new that you can do with the flowing space version of relativity in Gullstrand-Painlevé coordinates. The universe doesn’t change depending on the coordinate system you choose. Anything the flowing space relativity covers can (and has) been described in warped spacetime relativity.

The approaches are each applicable to Einstein’s relativity. They make exactly the same predictions about reality, but they’re mutually incompatible. Space doesn’t flow in warped spacetime relativity, and spacetime isn’t warped in flowing space relativity. You have to pick one or the other for any particular problem you tackle in relativity, not both at the same time.

Does relativity geometrize gravity? Einstein didn’t think so. Attributing the cause of gravity to being the geometry of space would be much like saying the streets of New York City are on a grid because space is an inherently Cartesian coordinate system. The choice of a coordinate system can’t cause anything; it just provides a way to describe the effects of gravity.

Nor, I’m sure, would Einstein have said that gravity is flow, despite the fact that you can use a flowing space model to describe gravity’s effects as well as you can with the geometry of warped spacetime.

Well then, what is gravity? This might seem like a cop out, but as I see it, gravity is whatever relativity describes. Beyond that, I’ll follow Tyson’s lead — I’m not really sure what gravity is.

Whether you choose to think in terms of the geometry of warped spacetime or flowing space is up to you. Whichever one makes the math easier for the problem you’re considering is probably your best bet.

When it comes to calculating black hole event horizon sizes, for example, you could turn to this collection of warped spacetime approaches, by some of the leaders in the field of general relativity, titled The Schwarzschild metric: It’s the coordinates, stupid!

I humbly suggest flowing space for finding event horizons instead. It’s at least one case where general relativity becomes trivially easy when you don’t think of gravity as geometry.

*see footnote 18

***

Take a look at my books for more on gravity and flowing space relativity. Sign up below to join my email list.