The Black Hole in Your Kitchen Sink, Part 3 -Gravitational Lensing

One of the first confirmations that Albert Einstein got gravity right with his theory of relativity was his description of gravitational lensing. It’s the distortion of things we see in space due to massive objects like stars, galaxies, and black holes.

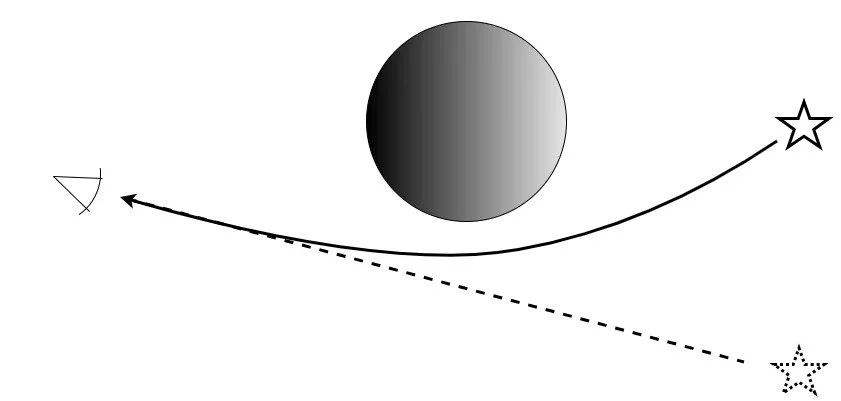

In particular, if a star is somewhere beyond a massive object, the star’s location in the sky will appear to be shifted from where it would appear if the massive object weren’t there.

The location of a distant star appears shifted away from its actual location due to light curving around a massive object.

You can test the effect in your own at-home gravity lab. To start, make a liquid version of a white hole as we did in my prior post on kitchen sink gravity experiments. (You can see in my first kitchen sink post that a white hole is a black hole running backward in time. So black holes and white holes are effectively the same thing, for the purposes of these demos.)

I improved the setup a bit in the video below by placing an upside-down tray under the stream.

The tray is more uniformly flat than my sink basin. It also has a very small ridge around the edge, which creates a nicely uniform and thin layer of water that works well for these sorts of experiments.

(The tray in these images and clips is IKEA item number 16382. The tray doesn’t seem to be stocked at IKEA anymore, although it’s available from private sellers on Ebay, if that matters to you.)

By gently flicking the water, I created waves that rippled past the kitchen sink white hole.

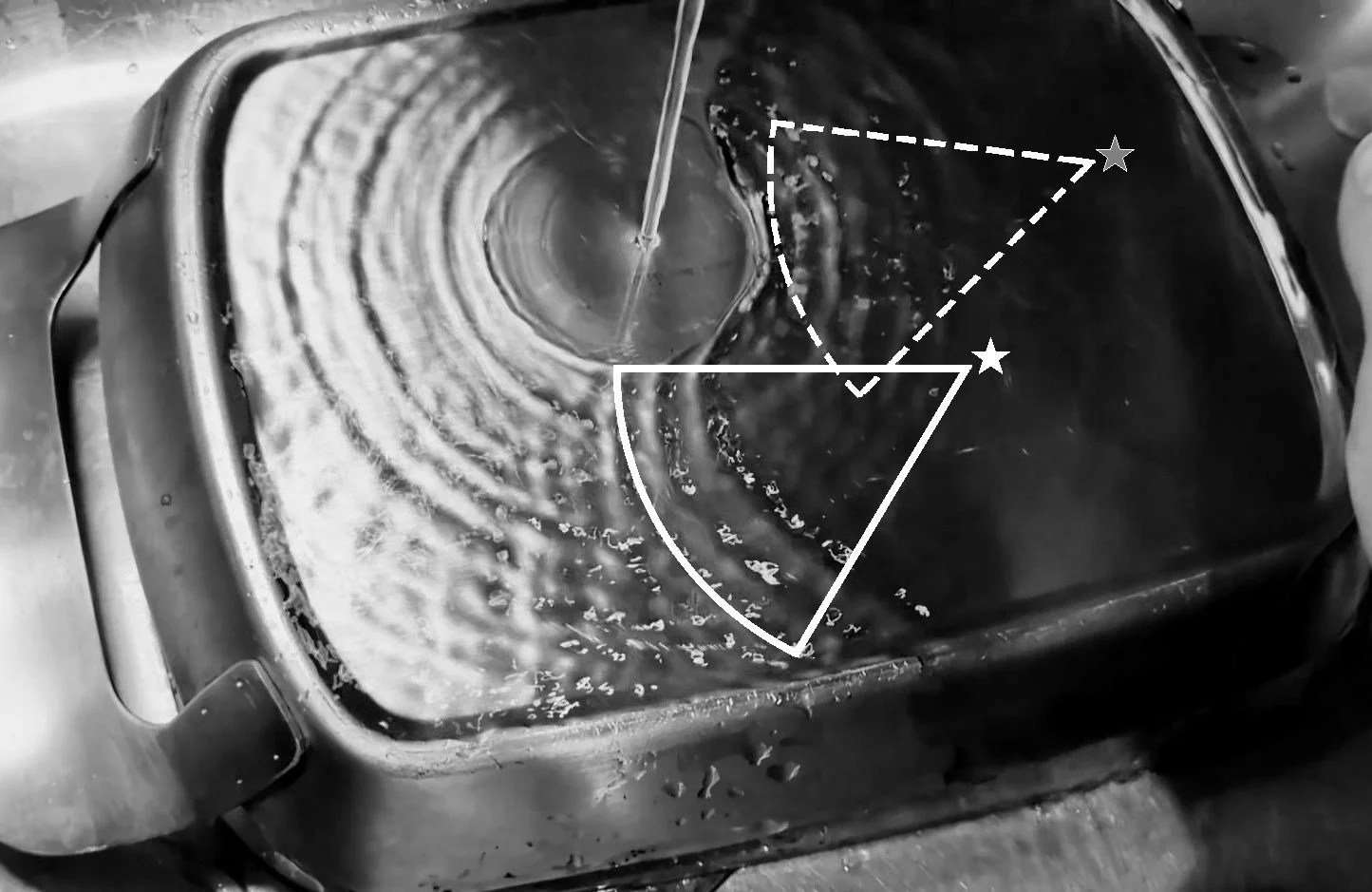

It’s a bit tricky to see, but the waves wrap around the white hole as they pass it. I tried to make it clearer by taking a frame grab of the video above, converting it to a higher contrast gray-scale image, and outlining the waves near the white hole.

That apparent location of the wave source shifts as the ripples wrap around a kitchen sink white hole.

The gray star shows roughly where I flicked the water to get the waves going. The white star indicates where the waves appear to have originated, based on the shape the waves take on as they wrap around the white hole.

This is a liquid version of the famous Eddington experiment in 1919, when Arthur Eddington measured the shift in apparent location of a star during a solar eclipse. He needed an eclipse to black out the sunlight in order to observe the star close to the Sun in the sky.

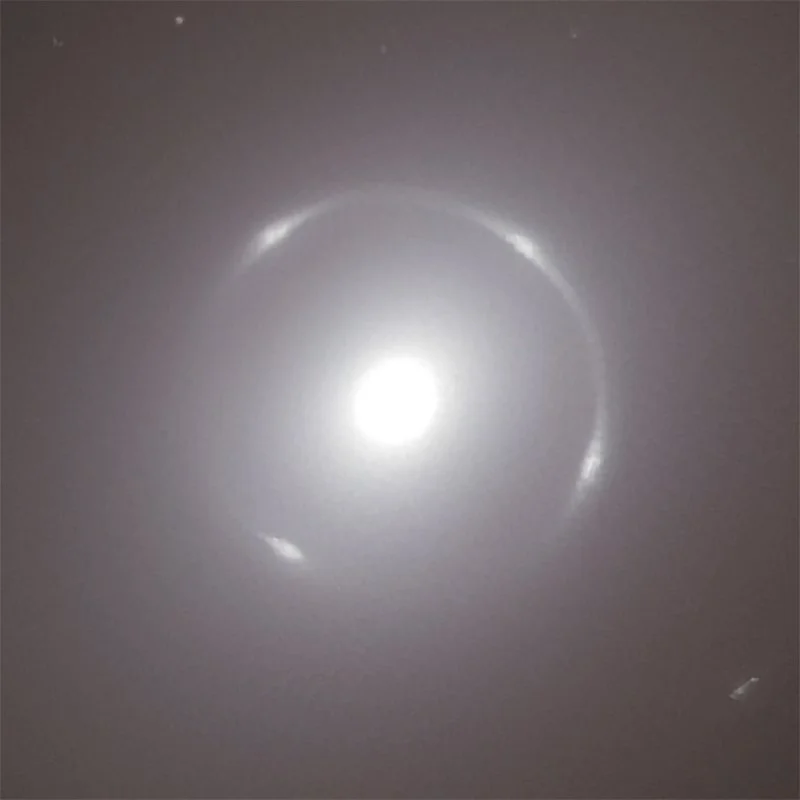

In some cases, when a bright light source is directly beyond a massive object, astronomers have found that gravitational lensing creates a pattern called an Einstein Ring. If the alignment is just right, light from the distant source is smeared out into a ring, rather than simply shifting in position.

Einstein Ring around the galaxy NGC 6505, captured by the European Space Agency’s Euclid space telescope.

We can’t make a full ring in a kitchen sink lab because it’s a thin layer of water rather than 3-D space. But it’s possible to make a 2-dimensional version of the effect.

If you set up the experiment so that the ripples pass both above and below your kitchen sink white hole at the same time, you should see the waves wrap around each side simultaneously.

Capturing the waves in action is challenging with my amateur lighting at home. Here’s my attempt at a slow-motion video of ripples that are a 2-D kitchen sink version of an Einstein ring.

The liquid analog of light from a star (water waves) is deflected as it passes around the liquid white hole. That makes the waves take on the shape they would have if they came from two separate sources.

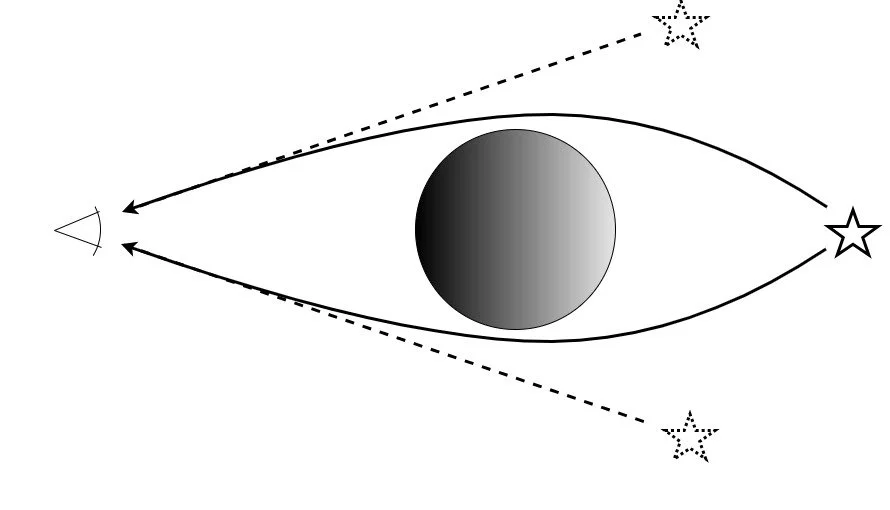

In the form of a diagram, this is what’s happening.

An observer at the location of the eye on the left in the diagram sees waves that appear to come from the two dashed stars, instead of the solidly outlined star at the place where I flicked the water.

I call these Einstein dots, rather than rings, because the interaction of the waves with the white hole effectively splits the liquid image of a star into two stars in the kitchen sink experiment.

The similarities between the flow of water in your sink and the deflection of light around black holes or other massive objects is more than a coincidence. In both cases, the equations of Einstein’s relativity describe them.

The parallels are particularly clear in an interpretation of relativity called the river model of black holes. You can read about it on the entertaining website of University of Colorado physicist Andrew Hamilton.

When you do the sorts of at-home experiments described here, you’re testing relativity much as Eddington did on his expedition from England to West Africa to observe an eclipse. Hopefully, your kitchen isn’t that far away.

***

For a deeper dive into the river model (also called the flowing space interpretation of relativity), take a look at my book Very Easy Relativity. Or subscribe to my email list, and I’ll send you a PDF for free. Just click the “Send me the PDF” option in the form below.