The Black Hole in Your Kitchen Sink, Part 2 -Experiments

So you’ve made your own (backward) black hole in your kitchen sink. Now what?

It’s time to play . . . I mean, perform serious science experiments!

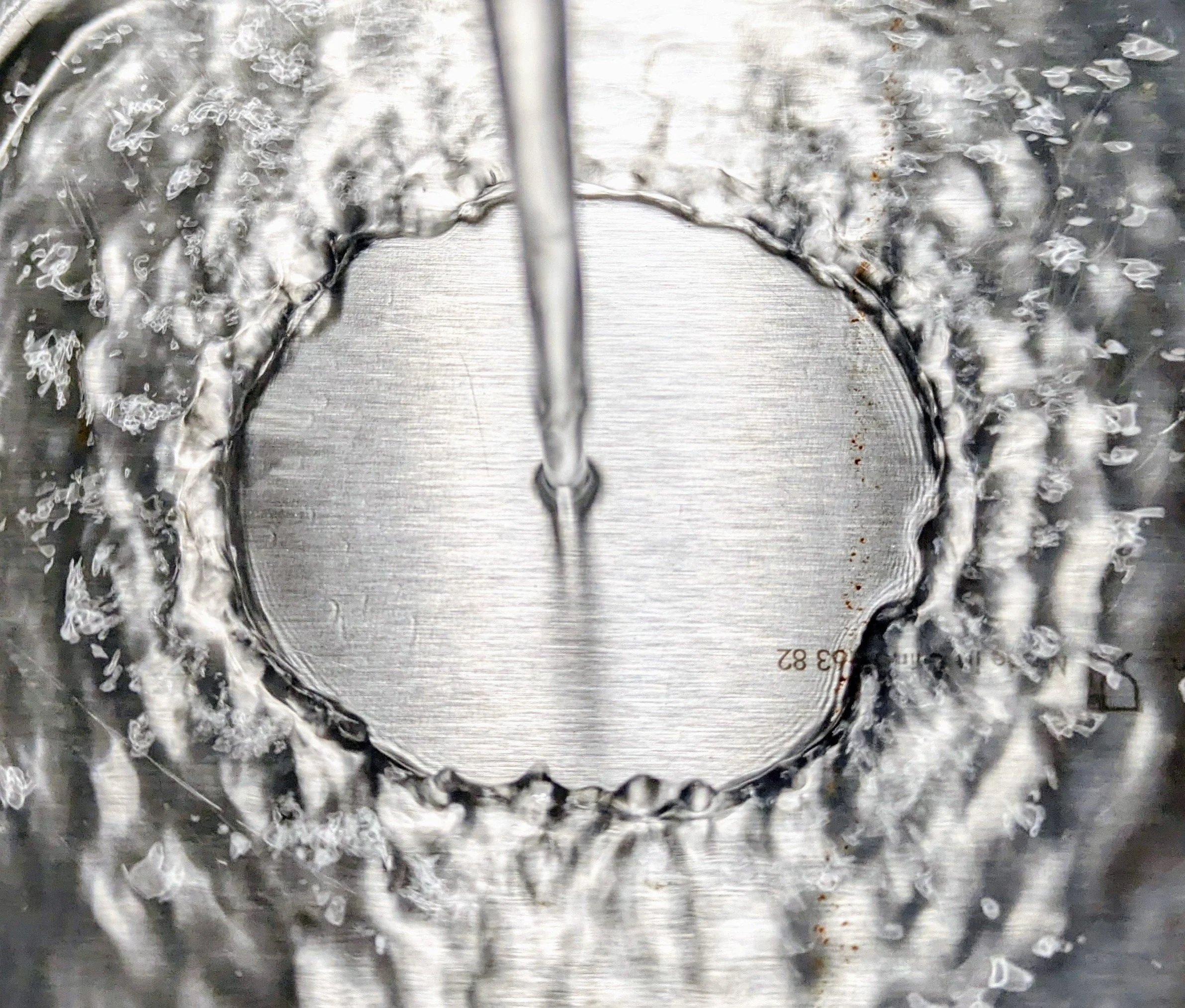

If you’ve done everything right so far, you should have something that looks like this.

This requires clearing out a space in your sink, turning on the water to a nice, smooth stream, and there you have it — a black hole running in reverse. Also known as a white hole.

The smooth, circular region is where water flows rapidly. That represents the interior of a white or black hole. The outer, burbly region is comparable to the open space surrounding the hole. And the ridge separating the two is like the event horizon that marks the point of no return separating the inside from the outside.

This is a fluid analog where water takes the place of space in the universe. Waves in the water play the part of light traveling through space. And the stream of water in the middle is comparable to the infinitely dense center of a black hole.

In the smooth center, water flows faster than waves can travel. That flattens out the ripples much as stretching a crumpled bed sheet can smooth out wrinkles.

There’s water between the stream at the center and the ripply region surrounding it. It’s just flowing so fast, and the waves are smoothed so much, that it’s hard to see.

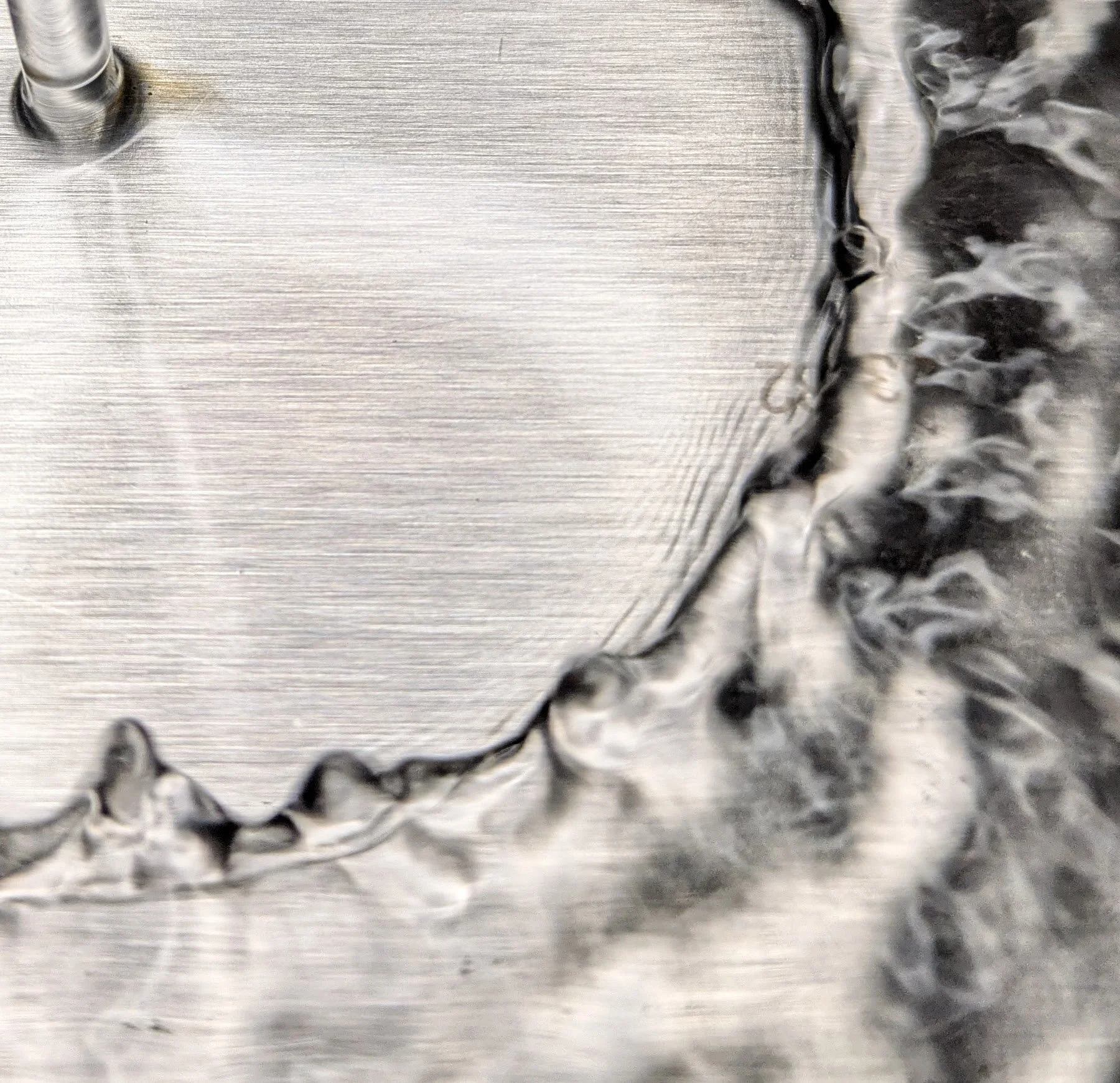

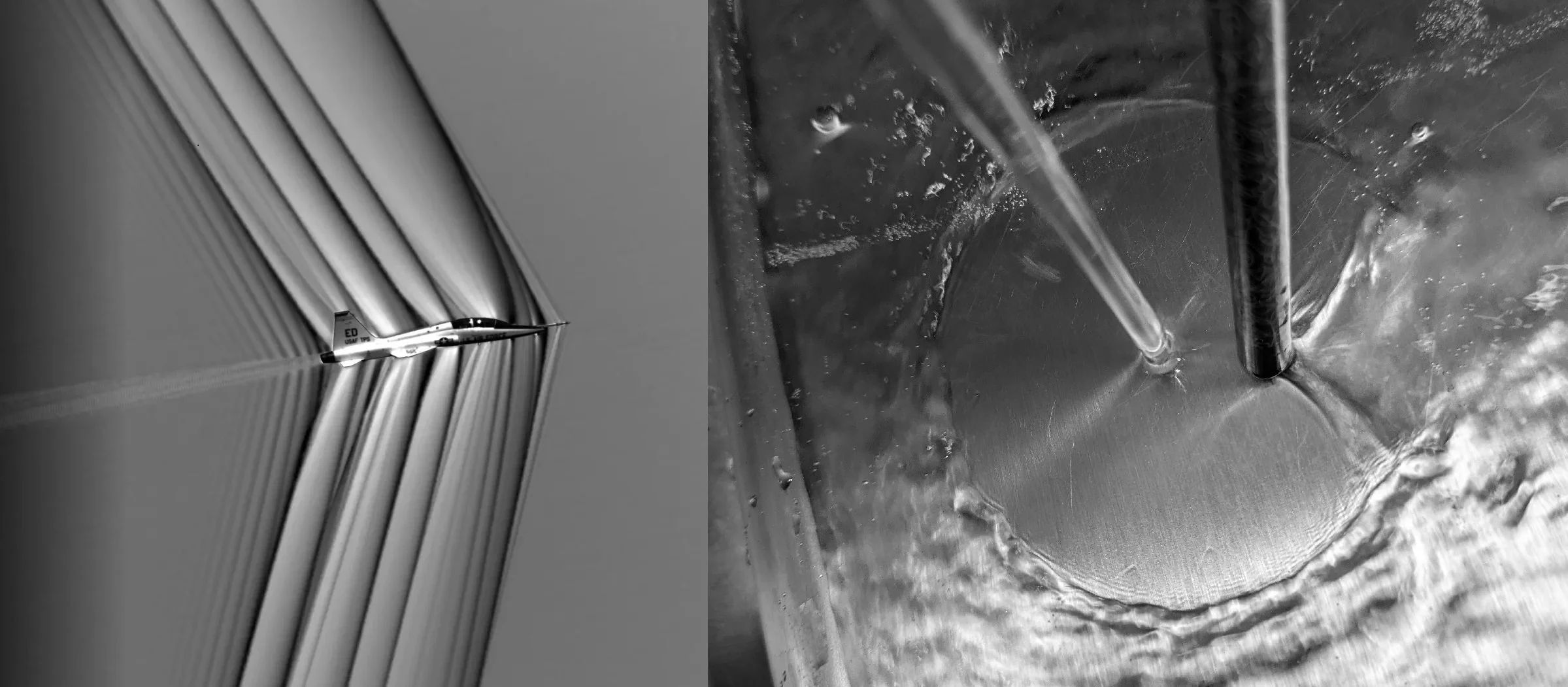

Poke it with a stick, though, and you’ll slow the water to make it appear. (I used a chopstick to probe the fast-flowing water in the image on the right below.) As you move it around, you’ll see that it makes a distinctive V-shape.

That shape is called a Mach wave. Supersonic airplanes do the same thing in the air. For planes, the wave forms when the aircraft travels faster than the speed of sound in air. For my chopstick, it happens when water flows faster past the stationary stick than the speed that waves can move in the water.

In black and white holes, according to an interpretation known as the river model of relativity, space itself flows faster than light inside the holes. If you had a magic chopstick that could poke the inside of one of a black or white hole, the same V-shaped pattern would form, except it would be made of flowing space instead of water.

The lack of magic chopsticks, or ways to slice black holes in half, means the best we can do to understand how they work is to do experiments with things like kitchen sink black holes.

Besides the chopstick test, one of the simplest experiments shows what happens to anything that might manage to get into a white hole. In the video below, I let a drop of red dye fall close to the center of my kitchen sink white hole.

The red dye is hurled out of the liquid white hole to the slower-flowing water beyond. A white hole would do the same, spewing light and matter into space.

So far, there doesn’t seem to be any sign of real white holes in the universe, at least as far as our telescopes can see. But, as described in Part 1 of the kitchen sink black hole post, a white hole is just a black hole running backward in time.

Thanks to the magic of budget cinematography, reversing time is easy enough for clips like this. (I used Reverse Magic Fx on my Android phone to make clips run backward.)

Below is a clip, running backwards, of a white hole. That makes it a kitchen sink black hole!

This kitchen sink experiment shows what it might look like if a cloud of dust got too close to a black hole in space. The analogy breaks down at the end, when the droplet of dye goes shooting upwards. But, hey, no analogy is perfect.

There are lots of other kitchen sink experiments you can do to get an idea of what happens when gravity gets extreme around black and white holes. I’ll post more in the future.

In the meantime, you can spend some time at a sink playing around in your own liquid version of an extreme gravity lab.

~James Riordon