Snakes: Nature’s Gravity Experiment

Adapted from Chapter 2 of Crush: Close Encounters with Gravity.

How does gravity affect your body? You could probably guess a few ways.

For one thing, your bones have to be strong enough to withstand walking, running, and jumping. No doubt, our digestive systems, nerves, and brains are specifically adapted to life at one g as well.

To know for sure how gravity has influenced the development of terrestrial creatures (including humans), we could put test subjects in environments with different levels of gravity to see how they evolve.

Evolution, though, is slow. It can take tens of thousands of generations for species to adapt to mildly different environments. Fortunately, Nature has already done the experiment for us — with snakes.

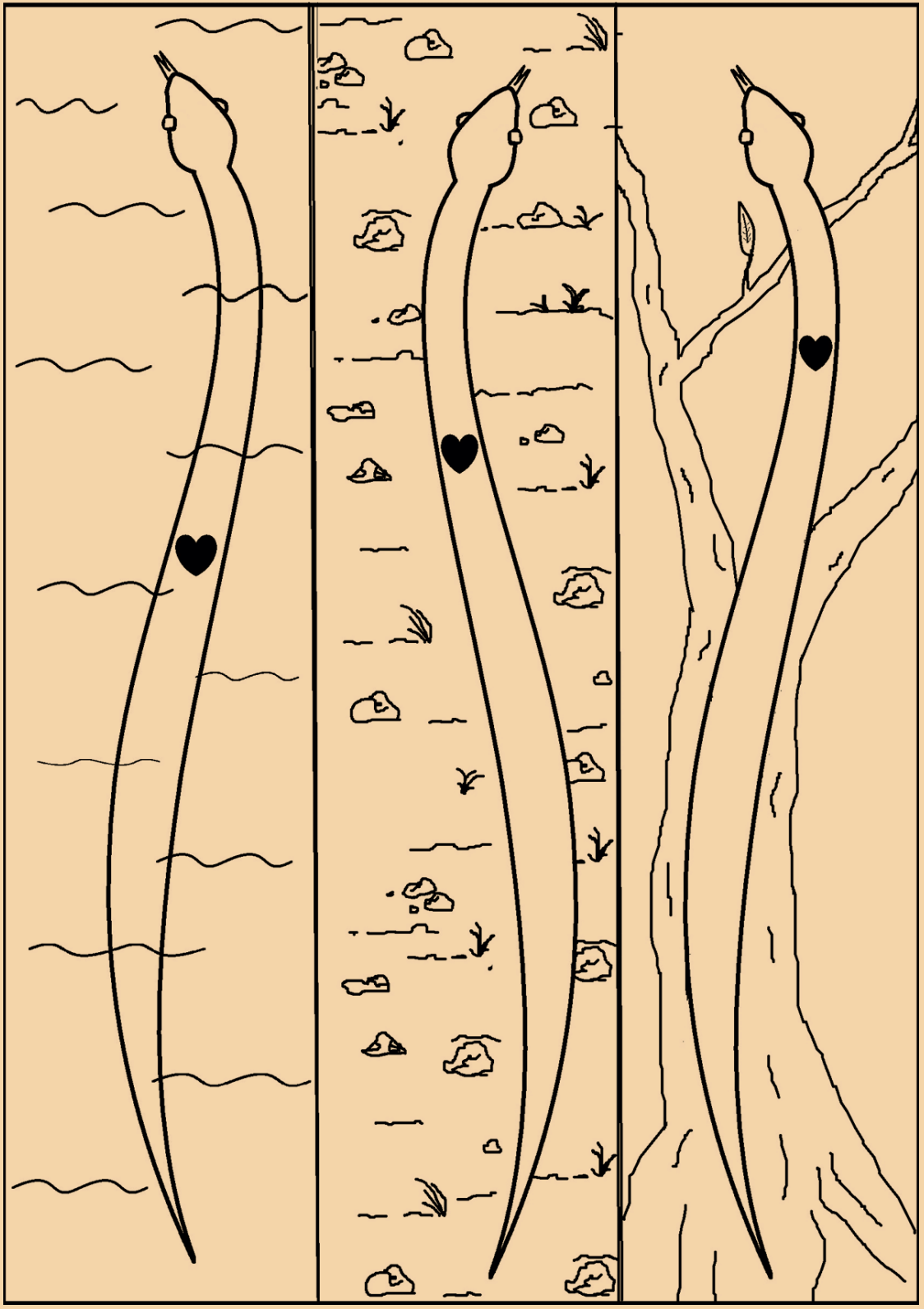

A sea snake (left) has a heart located roughly midway along its body. A tree snake (right) needs its heart to be close to its head to ensure it gets enough oxygen to its brain so it won’t faint as it climbs. A ground snake (middle) splits the difference, with its heart farther forward than a sea snake, but not as far forward as a tree snake. Researchers propose that the various arrangements are due to the effect of gravity on snake evolution.

~ illustration by Mary May Heil

In 2012, researchers at the University of Florida found that the positions of a snake’s internal organs seem to show adaptations to the strength of gravity that the snakes need to deal with.

Sea snakes, for example, don’t interact with gravity much at all. Their bouyancy in water almost perfectly offsets the downward pull of gravity. As a result, sea snakes spend their entire lives in the equivalent of weightless free-fall.

A highly venemous yellow lipped krait enjoys perpetual freefall as an ocean dwelling sea snake. Credit: Craig D

When the researchers looked at the arrangement of snake organs, they found that sea snakes had their hearts located roughly a the midpoint of their bodies, when measured from snout to tail. The central position of their hearts ensures uniform blood pressure and efficient blood flow throughout a sea snake’s length.

Tree snakes, on the other hand, frequently battle the full intensity of gravity as they ascend into forest canopies. If a tree snake had a centrally-located heart, climbing up a trunk would allow blood pressure to rise in its tail end and fall in its head. The result would be reduced blood flow and a lack of oxygen to its brain, which would potentially make a snake lightheaded, or perhaps even cause them to faint.

Climbing tree snakes have their hearts close to their heads to provide ample blood and ozygen to their brains even while climbing striaght up a trunk.

Passing out would be bad news for a snake, particularly if it’s high in a tree. To offset dizzying blood flow problems, tree snakes have hearts nearer to their heads than water snakes (see the third snake in the sketch above). The arrangement allows their hearts to more easily fight gravity to keep the blood pressure and oxygen levels up in their brains, rather than pooling in their tails.

Snakes that spend most of their time on the ground have to fight gravity on occasion, as they slither over hills or rise up to strike. But their nearly horizontal lifestyle keeps blood pressure challenges in check.

Coleslaw, my daughter’s corn snake, enjoys climbing, but has the heart of a ground snake.

A ground snake’s struggle with gravity lies somewhere between water snakes, who live in effective zero g, and tree snakes climbing vertically against the full force of gravity. Sure enough, the researchers found, snakes that mostly creep along the ground have hearts that are midway between the central hearts of sea snakes and the more forward hearts of tree snakes.

It’s a tidy little experiment — nearly identical creatures left to evolve under different intensities of gravity to reveal how their bodies adapt. All it took was hundreds of millions of years to do it.